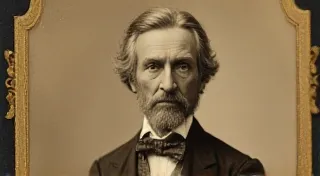

The Daguerreotype: A Pioneer in Photography

The daguerreotype stands as a monumental achievement in the history of photography, marking the first commercially successful photographic process. Before digital photography, before even roll film, there was the daguerreotype, a unique and beautiful image painstakingly created on a silvered copper plate. This article will explore its creation, the equipment involved, and the profound impact it had on the world.

The Birth of an Image: Louis Daguerre and Nicéphore Niépce

The story of the daguerreotype begins with a collaboration. Nicéphore Niépce, a French inventor, is credited with creating the earliest known surviving photograph in 1826, using a bitumen-coated pewter plate and an exposure time of eight hours! While a significant breakthrough, this process wasn't practical for widespread use. The very concept of how these early photographers captured images is remarkable; imagine the patience required for such lengthy exposures. Niépce sadly passed away in 1833, leaving his research unfinished.

Enter Louis Daguerre, a stage designer and artist who partnered with Niépce to further develop the process. After Niépce’s death, Daguerre continued the experimentation. Through meticulous refinement, Daguerre managed to shorten the exposure time considerably and dramatically improve image quality. This involved not just chemical adjustments, but a deeper understanding of optics and the behavior of light. It’s fascinating to consider how early advancements in lenses, even relatively simple ones, played a vital role in the daguerreotype's success. In 1839, Daguerre announced his invention, the daguerreotype, to the French Academy of Sciences.

The Process: A Delicate Craft

Creating a daguerreotype was a complex and time-consuming process requiring specialized equipment and considerable skill. The process typically involved the following steps:

- Plate Preparation: A sheet of silver-plated copper was meticulously polished. Achieving a perfectly smooth and reflective surface was paramount; any imperfections would show in the final image.

- Sensitization: The plate was then sensitized by exposing it to iodine vapor, creating a layer of silver iodide. This stage required precise control of humidity and temperature to ensure a uniform coating.

- Exposure: The sensitized plate was placed in a camera, and the subject was exposed to light. Exposure times could range from several minutes to half an hour, depending on the lighting conditions. This reliance on ambient light meant that daguerreotype portraits were typically posed and carefully lit, a far cry from the spontaneous snapshots we take today. The early cameras themselves were quite primitive, a far cry from the sophisticated devices we have now; a detailed look at the evolution of camera lenses reveals just how far photographic technology has advanced.

- Development: After exposure, the plate was developed using mercury vapor, revealing the latent image. This was arguably the most dangerous stage, due to the toxicity of mercury.

- Fixing: The image was then fixed using a solution of sodium thiosulfate (originally hyposulfite of soda), to remove the remaining light-sensitive silver iodide and make the image permanent. Without this final step, the image would quickly degrade.

The resulting image was a unique, highly detailed, and laterally reversed view on a reflective silver surface. Because each plate produced a single, one-of-a-kind image, daguerreotypes could not be easily reproduced. This meant that a daguerreotype was truly a treasured possession, unlike the mass-produced photographs available today.

Equipment of the Daguerreotypist

A daguerreotypist's toolkit was a fascinating collection of specialized equipment:

- Camera: Typically a wooden box with a lens – often simple and lacking the complex features of modern cameras. Early camera designs were often crude, reflecting the nascent state of photographic technology.

- Lens: Usually a single lens, often with limited focusing capabilities. The clarity and sharpness of the image depended heavily on the quality of the lens, and early lenses were often a source of imperfection.

- Chemicals: Iodine, mercury vapor, sodium thiosulfate - highly toxic and dangerous chemicals requiring careful handling. The hazardous nature of these chemicals underscores the risks faced by early photographers.

- Darkroom: Essential for preparing and developing the plates, shielded from all light. Maintaining complete darkness was crucial for the delicate sensitization and development processes.

- Polishing Cloths: Crucial for the meticulous cleaning and polishing of the silvered copper plates. A pristine surface was vital for the final image's quality.

The Impact and Legacy: Beyond Portraits

The announcement of the daguerreotype in 1839 sparked a global sensation. Suddenly, portraiture, previously the domain of the wealthy who could afford painted portraits, became accessible to a much wider segment of society. This democratization of image-making was revolutionary, allowing ordinary people to preserve memories and appearances in a way never before possible.

However, the impact of the daguerreotype extended far beyond portraiture. Scientists and researchers quickly recognized the potential for documenting observations and discoveries with unprecedented accuracy. Botanists used daguerreotypes to record plant specimens, architects used them to document buildings, and explorers used them to capture landscapes. These early photographic records provided invaluable insights into the natural world and the progress of civilization.

The popularity of daguerreotypes also spurred innovation in related fields. The demand for better lenses and more sophisticated cameras led to advancements in optics and mechanical engineering. The need for reliable and consistent photographic chemicals drove the development of new chemical processes. It's easy to appreciate the ingenuity involved when considering the relative simplicity of the Hasselblad cameras of later eras, and comparing them to the very basic setups of the daguerreotypists.

The daguerreotype’s popularity quickly spurred competition, with alternative photographic processes emerging. The wet collodion process, for example, offered the advantage of producing multiple prints from a single negative, overcoming the limitations of the daguerreotype’s uniqueness. While other formats appeared, and photographic techniques were refined, the daguerreotype's role in shaping the visual landscape of the 19th century is undeniable.

The Unique Qualities of a Daguerreotype Image

What truly sets a daguerreotype apart is its unique aesthetic qualities. The image is not printed on paper; it’s directly formed on the silvered copper plate. This results in an image with exceptional detail and a remarkable three-dimensional appearance. The reflective nature of the plate also creates a softness and glow that is difficult to replicate with modern photographic processes.

Many daguerreotypes were encased in decorative cases, often made of leather or metal, which protected the fragile image and added to its value. These cases themselves became part of the daguerreotype’s history, often reflecting the style and taste of the era.

The daguerreotype’s contribution to the preservation of history is immeasurable. These fragile images offer a glimpse into the lives of people who lived over a century and a half ago, providing a connection to the past that is both tangible and profound.

While eventually superseded by the wet collodion process and later by dry plate photography, the daguerreotype holds a unique place in history. Its beautiful, one-of-a-kind images provide a fascinating glimpse into the 19th century, and its invention laid the foundation for the entire field of photography. The ability to capture moments in time, to preserve memories, and to document the world around us, owes its origins to the pioneering efforts of Louis Daguerre and Nicéphore Niépce, and to the dedicated craftspeople who mastered the delicate art of the daguerreotype.